Women make up the majority of the world’s 7.8 billion people, believe it or not. Paradoxically, numbers are not on their side, and women globally have only a fraction of the rights that men have. Despite tremendous attempts to change cultural norms and implement regulations to cut off gender discrimination against women, gender inequality in the workplace persists. For example, tech companies perpetuate a loop of hiring people of the same gender. Women hold only 26% of computer-related jobs, according to the most current women in the workforce data. The objective of this essay, on the other hand, is to investigate women’s presence in the workforce and demonstrate that, despite the obstacles, women are leaping over mountains and taking on the role of breadwinners.

Women make up the majority of the world’s 7.8 billion people, believe it or not. Paradoxically, numbers are not on their side, and women globally have only a fraction of the rights that men have. Despite tremendous attempts to change cultural norms and implement regulations to cut off gender discrimination against women, gender inequality in the workplace persists. For example, tech companies perpetuate a loop of hiring people of the same gender. Women hold only 26% of computer-related jobs, according to the most current women in the workforce data. The objective of this essay, on the other hand, is to investigate women’s presence in the workforce and demonstrate that, despite the obstacles, women are leaping over mountains and taking on the role of breadwinners.

Women in the Workplace Statistics

- 47.7% of the global workforce population is occupied by women.

- Canada has the highest female labour force participation rate at 61.3%.

- 2% of the college-educated workforce are women.

- A whopping 75% of self-employed women love their job.

- Only 27.1% of women are managers and leaders.

- 61% of women think motherhood disrupts their progress opportunities.

- For the past 20 years, the number of women software engineers has increased by just 2%.

- 42% of women claim they face gender discrimination in the workplace.

- 48% of women occupy entry-level roles.

- Work-life balance causes conflict for an astonishing 72% of women.

According to the World Bank’s Women, Business, and the Law 2022 report, around 2.4 billion working-age women are denied equal economic opportunity and 178 countries have legal barriers that prevent them from fully engaging in the economy. In 86 countries, women face occupational limitations, while 95 countries do not guarantee equal pay for equal work performed.

While progress has been made, the gap between men’s and women?s expected lifetime earnings globally is US$172 trillion – nearly two times the world?s annual GDP, said Mari Pangestu, World Bank Managing Director of Development Policy and Partnerships.

Women, Business and the Law 2022 measures laws and regulations across 190 countries in eight areas impacting women’s economic participation,mobility, workplace, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets, and pensions. The data offers objective and measurable benchmarks for global progress towards gender equality. Just 12 countries, all part of the OECD, have legal gender parity.

Women cannot achieve equality in the workplace if they are on an unequal footing at home, said Carmen Reinhart, Senior Vice President and Chief Economist of the World Bank Group. Women raising children pay a motherhood penalty in underemployment, slower career progression, and lower lifetime earnings. The increased burden of unpaid childcare borne by mothers and women, raising children during the pandemic, was a key driver of the disproportionate effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on women?s employment outcomes overall.

Juggling paid work with these additional demands caused women raising children to reduce their contribution to the labour market, and in some cases leave the workforce altogether.

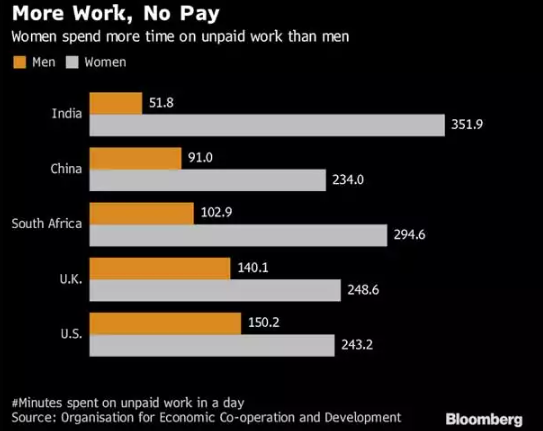

Women Spend More Time Performing Unpaid Work, Such as Childcare and Housework, unlike Men.

Globally, only 41 million (1.5%) men provide unpaid care on a full-time basis, compared to 606 million (21.7%) women.

- Women are less likely to be employed compared to Men, including women without children.

On average across the globe, women spend 4 hours and 22 minutes per day in unpaid labour, compared to only 2 hours and 15 minutes for men.

- Covid-19 has widened this gap even further. Women are now spending 15 hours more in unpaid labour each week than men.

Despite the global pandemic’s disproportionate impact on women’s lives and livelihoods, 23 countries changed their laws in 2021 to take forward steps toward increasing women’s economic participation. Across the world, 118 economies guarantee 14 weeks of paid leave for mothers. More than half (114) of the economies measured mandate paid leave for fathers, but the median duration is just one week.

In the past year, Hong Kong SAR, China which previously provided 10 weeks of paid maternity leave?introduced the recommended 14-week minimum duration. Armenia, Switzerland, and Ukraine introduced paid paternity leave. Colombia, Georgia, Greece, and Spain introduced paid parental leave, which offers both parents some form of paid leave to care for a child following birth. Laws promoting paid leave for fathers can reduce discrimination in the workplace and improve work-life balance.

Regional Highlights

- Greece, Spain and Switzerland reformed laws in 2021, all focusing on improving paid leave for new parents. Twelve advanced economies are the world’s only economies that score 100, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain and Sweden.

- Two economies from East Asia reformed last year. Cambodia introduced an old-age pension system that sets equal ages at which women and men can retire with full pension benefits. Vietnam eliminated all restrictions on the employment of women.

- Armenia and Ukraine introduced paid paternity leave and Georgia introduced paid parental leave. Ukraine also equalized the ages at which women and men can retire with full pension benefits.

- Argentina explicitly accounted for periods of absence due to childcare in pension benefits. Colombia became the first country in Latin America to introduce paid parental leave, aiming to reduce discrimination against women in the workplace.

- Bahrain mandated equal pay for work of equal value and lifted restrictions on women?s ability to work at night. It also repealed provisions giving the relevant authority the power to prohibit or restrict women from working in certain jobs or industries.

- Egypt enacted legislation protecting women from domestic violence and made access to credit easier for women by prohibiting gender-based discrimination in financial services.

- Kuwait prohibited gender discrimination in employment and adopted legislation on sexual harassment in employment.

- Lebanon enacted legislation criminalizing sexual harassment in employment.

- Pakistan lifted restrictions on women’s ability to work at night.

- Gabon stands out, with comprehensive reforms to its civil code and the enactment of a law on the elimination of violence against women. These reforms gave women the same rights to choose where to live as men, get jobs without permission from their husbands, removed the requirement for married women to obey their husbands and allows women to be head of the household in the same way as men.

- Gabon granted spouses equal rights to immovable property and equal administrative authority over assets during the marriage. Gabon also enacted legislation protecting women from domestic violence. Gabon’s reforms gave women the same rights to open a bank account as men and prohibited gender-based discrimination in financial services.

- Angola enacted legislation criminalizing sexual harassment in employment.

- Benin removed restrictions on women’s employment in construction so that women can now work in all the same jobs in the same way as men.

- Burundi mandated equal remuneration for work of equal value.

- Sierra Leone made access to credit easier for women by prohibiting gender-based discrimination in financial services.

- Togo introduced new legislation which no longer prohibits the dismissal of pregnant workers, reducing women?s economic opportunities.

The Global View

Although globalisation has brought millions more women into paid labour, men continue to outnumber women in the labour force. Gender inequality has also driven women to the bottom of the global value chain, with few or no opportunities for decent opportunities and job security.

Women account for half of the world’s potential, which must be realised through equal access to respectable, high-quality paid labour, as well as gender-sensitive legislation and practises such as adequate parental leave and flexible hours. If women performed the same role in labour markets as men, the global annual Gross Domestic Product might rise 26% significantly, by 2025.

Source: Our World in Data

Across the world, women were more likely than men to lose jobs during the pandemic and their recovery has been slower. Policy changes that address gender disparities and boost the number of working women improved access to education, child care or flexible work arrangements, for example , would help add about $20 trillion to global GDP by 2050, according to Bloomberg Economics.

Women Workforce in India

India is running out of time to reap the economic gains. The collapse in Female Labour Participation (FLP) in the labour force has sparked concern. There has been a lot of talk regarding the recent drop in Female Labour Force Participation rates (FLPRs).

According to a World Bank report, the number of working women in India declined from 26% to 19% between 2010 and 2020.

According to data from the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation (MoSPI), India ranks far behind other African and Asian countries in terms of FLP (Female Labor Participation) in labour force.

As viruses proliferated, an already dire situation worsened: experts in Mumbai predicted that female employment would drop to 9% by 2022.

If the ILO projections are any indication, the FLPR is slated to fall to 24% by 2030 which will certainly detract India from achieving SDG 5 (sustainable development goal number 5) eliminating gender inequalities by 2030.

The Labour Force Participation Rate indicates the number of women of working age seeking employment; it includes both employed and unemployed job seekers. India has one of the world’s lowest percentages of female involvement (21 per cent ).To put it another way, 79% of Indian women (aged 15 and up) do not even seek a job.

Women’s participation rates are two to three times greater in nations with which India is frequently compared, such as China, the United States, Indonesia, and Bangladesh. The decline in workforce participation is partly about culture. Doing nothing risks derailing the country’s efforts to become a competitive producer for global markets. Even though women constitute 48% of the population in India, they contribute just around 17% of GDP, compared to 40% in China.

Image Source: Bloomberg

The debate about women’s low labour-force participation should centre on how the burden of domestic tasks and caregiving work is distributed between the genders.

According to OWID (Our World in Data) data from 2014, India has the third highest female-to-male ratio of unpaid care labour hours at 9.83. As a consequence, in 2017-18, 62.1 per cent of women aged 15 to 59 participated in domestic tasks. Women’s ability to participate in the labour market is hampered by cultural norms that place them in charge of routine household chores.

The study also shows that women bearing domestic responsibilities are willing to work regularly, provided their commitments can be fulfilled from home. Another study conducted in West Bengal by Kabeer and Deshpande discovered that 73.5 per cent of unemployed women are interested in work opportunities. However, the vast majority of them (67.8 per cent) anticipate working part-time.

The statistics reveal how cultural norms in India influence female labour supply responses to economic opportunity. Women are not in a position to neglect their domestic obligations, despite their desire, they can only take up opportunities that allow them to combine paid and unpaid work.

Image Source: The Print

Aside from resource constraints, there is a considerable unmet need for female labour supply in the country. Women have been disproportionately affected by the Indian economy’s unemployment rise. Between 2012 and 2018, India’s working-age population increased by 65 million men and 63 million women. The LFPR (Labour Force Participation Rate) for men remained steady, but the LFPR for women decreased, showing that the labour market could accommodate a rising number of male employees but not female workers.

For two reasons, women have borne the brunt of this increase.

- First, agricultural mechanisation, such as seed drills and threshers, has reduced manual labour, which was primarily performed by women.

- Second, India’s industrial sector has not generated labour-intensive employment that women who have been displaced from agriculture might fill.

As a result, India’s growth story is fraught with complexities. On the one hand, there has been a lack of labour-intensive growth, structural reform, and formalisation, while caste dynamics and social norms continue to regulate labour mobility. The combination of these distinguishing characteristics of the Indian economy has resulted in unequal gender diversity in the workplace. This market failure’s loss impacts not just Indian women, but the whole economy. After all, half of the individuals who could contribute to the country’s growth are unable to do so.

Ratio of female to male labor force participation rate (%) (modeled ILO estimate)

| Country | 1990 | 2019 | Absolute Change | Relative Change |

| India | 35.73% | 27.38% | -8.34 pp | -23% |

| Canada | 76.18% | 87.15% | +10.98 pp | +14% |

| New Zealand | 71.92% | 86.99% | +15.07 pp | +21% |

| United Kingdom | 70.20% | 85.38% | +15.17 pp | +22% |

| United States | 74.64% | 82.75% | +8.11 pp | +11% |

Source: Our World in Data

In recent years, government policies were aimed at addressing the falling FLPR have mainly focussed on launching employment programmes with special provisions to incentivize female employment such as:

- MGNREGA; Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency (MUDRA);

- Launching special skill training programmes; and heavy investment programmes that support the education of girl children.

- Working Women Hostels for ensuring safe accommodation for working women away from their place of residence.

- Support to Training and Employment Program for Women (STEP) to ensure sustainable employment and income generation for marginalized and asset-less rural and urban poor women across the country.

- Rashtriya Mahila Kosh (RMK) provides microfinance services to bring about the socio-economic upliftment of poor women.

- National Mission for Empowerment of Women (NMEW) to strengthen the overall processes that promote the all-round development of Women

- Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act, 2017

- Prevention of Sexual Harassment Act at Workplace, 2013

Persisting challenges

Gender roles

Gender roles and the obligations placed on women to conform to them vary by geography, faith, and household. One way that conformity manifests itself is through marital status. Women with a spouse, for example, are less likely to be working or actively pursuing employment in both developed and developing nations. This can be induced by the economic stability of a partner’s wage, which can perpetuate the “male breadwinner” bias in some couples. In developing countries, the contrary is true: economic necessity pushes all women to work, regardless of marital status.

Work-family balance

Women and men both believe that the most difficult hurdle for women in a paid job is balancing it with family duties. Work like childcare, cleaning, and cooking are vital for the well-being of a home ? and hence for the well-being of societies as a whole ? yet women continue to bear the burden of this often unseen and underestimated job.

Lack of transport

The absence of safe and accessible transportation is the most difficult problem for some women who report being affected in underdeveloped and emerging nations. On their everyday commute, women are all too often subjected to harassment and even sexual assault.

Sexual Harassment

According to the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB), 3.59 lakh complaints of sexual harassment against women were filed in 2017. Women’s career choices and job participation decisions might be influenced by safety concerns. Gender-based violence and harassment at work escalated throughout the epidemic, severely impairing women’s capacity to work.

Lack of affordable care

A shortage of affordable and accessible daycare for children or family members is a global obstacle for women, both those seeking employment and those who are currently working. It reduces a woman’s chances of getting married by about 5 percentage points in impoverished nations and 4 percentage points in developed countries (data from the World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends for Women 2017).

Bridging the gap

Flexible working options

Flexible working options must be provided to and used equally by men and women, such that flexible working is accepted as standard practise and there are no conscious or unconscious gender biases against those who work flexibly.

Affordable childcare

More affordable childcare choices are required to assist minimize the unpaid care load faced by women. According to one research, the installation of free child-care facilities in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, nearly quadrupled the employment rate of moms (who were not working prior to getting this benefit) from 9% to 17%

Equal paid parental leave

The Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act of 2017, which increased paid maternity leave from 12 to 26 weeks, has the unintended consequence of preventing businesses from hiring more women. The lack of similar benefits for fathers creates bias against female employees. As a result, governments and businesses must implement equal paid parental leave laws to help distribute women’s unpaid care burden. This will increase women’s participation in paid labour and provide more opportunities for advancement. This will also help to bridge the pay gap between men and women.

Creating a Safe Work Environment

All employees should be able to work in a safe and healthy setting. Every female employee should be given a forum to voice their concerns. Laws and rules pertaining to women’s safety in organisations should be strictly enforced. Every enterprise and factory that employs women should have a zero-tolerance sexual harassment policy. Creating an Internal Committee (IC) to address sexual harassment concerns in businesses and put rules in place to protect women at work.

Conclusion:

Women must be equal participants in schools, health care, financial systems, legal institutions, and families in order to be equal partners in society. To improve women’s status, societal standards must change, from condoning domestic abuse to feeling it is wrong for women to work outside the home.

References:

- https://teamstage.io/women-in-the-workforce-statistics/

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/03/01/nearly-2-4-billion-women-globally-don-t-have-same-economic-rights-as-men

- https://www.pwc.com/id/en/pwc-publications/services-publications/consulting/women-in-work-index.html

- https://indianexpress.com/article/business/economy/women-workforce-pandemic-unemployment-7948977/

- https://ourworldindata.org/female-labor-supply

- https://www.catalyst.org/research/women-in-the-workforce-india/

- https://teamstage.io/women-in-the-workforce-statistics/

- https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/indicators/no-place-for-women-what-drives-indias-ever-declining-female-labour-force/articleshow/83480203.cms?from=mdr

- https://interactive.unwomen.org/multimedia/infographic/changingworldofwork/en/index.html

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-06-02/covid-cut-india-s-women-out-of-the-job-market-now-90-aren-t-in-the-workforce

- https://www.zigsaw.in/jobs/women-safety-at-workplace/

For more blogs and articles, visit our official website. Contact us for workshops and queries related to POSH, EAP(Employee Assistance Program,) and Diversity and Inclusion.